Centuries before a Hollywood studio thought it would be a great idea to spend millions on a film about a girl travelling to fairy lands created through CGI, and before shopping malls and ad agencies thought it would be an equally great idea to pound the same classical melodies into the ears of shoppers year and after year, a poet and musician bent over his desk in Berlin working on a fairy tale. A story for children, perhaps—his daughter was about 11 at the time. A story about toys coming to life and fighting mice. But as he wrote, images of war and obsession kept creeping into his tale.

Much later, someone thought it would be a great idea to turn his fantasy about inescapable war into a ballet. Which later became inescapable music during the holiday season.

You might be sensing a theme here.

Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann (1776-1822) was born into a solidly middle class family in Königsberg, a city at the time part of Prussia and now part of Kaliningrad, Russia. His father was an attorney; his mother, who married at the age of 19, apparently expected to be a housewife. Shortly after Hoffmann’s birth, however, their marriage failed. The parents divided their children: older son Johann went with his father, and Ernst stayed with his mother and her siblings, who sent him to school and ensured that he had a solid grounding in classical literature and drawing.

The family presumably hoped that the boy would eventually enter some lucrative career. Hoffmann, however, hoped to become a composer—he had a considerable talent for music playing. As a partial compromise, he worked as a clerk in various cities while working on his music and—occasionally—cartoons. In 1800, Hoffmann was sent to Poland, where, depending upon the teller, he either flourished or got himself into trouble. In 1802, he married Marianna Tekla Michalina Rorer, a Polish woman; they moved in Warsaw in 1804, apparently willing to spend the rest of their lives in Poland.

Just two years later, Hoffmann’s life was completely disrupted by Napoleon, who had already conquered most of what is now Germany before continuing on to Poland. Hoffmann was forced to head to Berlin—also under Napoleon’s control—and spent the next several years juggling work as a music critic, theatre manager and fiction writer while trying to avoid war zones and political uprisings. Only in 1816, when the Napoleonic Wars were mostly ended, did he achieve major success with his opera Undine. Unfortunately, by then, he had developed both syphilis and alcoholism. He died just six years later.

Nussknacker und Mausekönig was written in that brief period of post-war success. Published in 1818 in Die Serapionsbrüder, it joined several other weird and wondrous tales, linked with a framing device claiming that these were stories told by friends of Hoffmann, not Hoffmann himself. By then, however, Hoffmann had written a number of other fantasies and fairy tales that sounded suspiciously like the ones in Die Serapionsbrüder, so almost no one, then or later, questioned the authorship of Nussknacker und Mausekönig.

As the story opens, Fritz and Marie (the more familiar name of “Clara” is taken from the name of her doll, “Madame Clarette”) Stahlbaum are sitting in the dark, whispering about how a small dark man with a glass wig has slipped into their house carrying a box. This would be kinda creepy if it weren’t Christmas Eve, and if the man in question weren’t Godfather Drosselmeier, the man who both fixes the household clocks and brings them interesting presents. Even as it is, given Hoffmann’s description of just how Godfather Drosselmeier fixes the clocks—by viciously stabbing them—it’s still creepy.

Anyway. This year, Herr Drosselmeier has created an elaborate dollhouse for them—a miniature castle, complete with a garden and moving people including one figure who looks rather like Herr Drosselmeier. The children are not exactly as appreciative as they could be. Partly because they are too young, but also because the castle can only be watched, not played with, and they want to play with their toys.

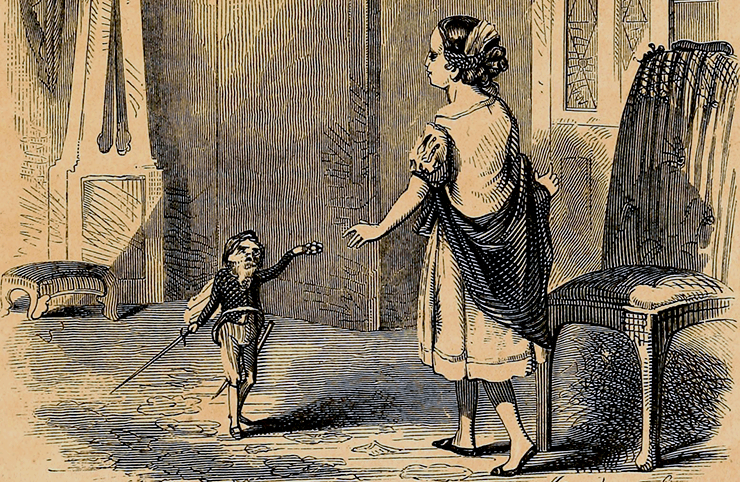

Fortunately, Marie also spots a nutcracker on a tree—a cleverly designed toy that can crack open nuts and also bears a rather suspicious resemblance to Herr Drosselmeier. She loves the little nutcracker, but unfortunately, Fritz puts just a few too many nuts into the nutcracker, breaking it, to Marie’s genuine distress.

Later that night, after everyone else has gone to bed, Marie stays down below, with all of the lights almost out, so that she can tend to the little broken nutcracker. In the light of the single remaining candle, the nutcracker almost—almost—looks alive. Before she can think too much about this, however, things get, well, weird—Herr Drosselmeier suddenly appears on the top of the clock, and Marie finds herself surrounded by fighting mice, one of whom has seven heads. The dolls wake up and start battling the mice. In the ensuing battle, Marie is injured—and nearly bleeds to death before her mother finds her.

As she recovers, Herr Drosselmeier tells her and Fritz the rather dreadful story of Princess Pirlipat, a princess cursed by the machinations of the vengeful Lady Mouserinks, who has turned the princess into an ugly creature who only eats nuts. Perhaps suspiciously, Herr Drosselmeier and his cousin, another Herr Drossmeier, and his cousin’s son, feature heavily in the story—a story that does not have a happy ending.

Marie, listening closely, realizes that the Nutcracker is that younger Herr Drosselmeier. Now identified, the younger Herr Drosselmeier/Nutcracker takes Marie to a magical fairyland inhabited by dolls and talking candy, where the rivers are made of lemonade and almond milk and other sweet drinks and the trees and houses are all formed of sugary sweets. (It is perhaps appropriate at this point to note that Hoffmann had faced severe hunger more than once during the Napoleonic Wars, as had many of his older readers.)

Right in the middle of all the fun, the Nutcracker drugs her.

Marie is, well, entranced by all this, so despite the drugging, the realization that the Drosselmeiers deliberately gave her a very real magical toy that led to her getting wounded by mice, and, for all intents and purposes, getting kidnapped, she announces that unlike Princess Pirlipat, she will always love the Nutcracker, no matter what he looks like.

And with that announcement, the young Herr Drosselmeier returns, bows to Marie, and asks her to marry him. She accepts.

They get married the following year.

Did I mention that when the story starts, she’s seven years old?

To be somewhat fair, time does pass between the start of the tale and its end, with Hoffmann casually mentioning that a couple of days had passed here, and a couple more days passed there, and one paragraph does give the sense that several days have passed. To be less fair, all of these days seemingly add up to a few months at most. And the story never mentions a second Christmas, which means that Marie is at most eight when she agrees to marry young Herr Drosselmeier and nine when she actually does.

He’s an adult—an adult who has spent some time as a Nutcracker, granted, but also an adult who drugged her in the earlier chapter.

If you are wondering why most ballet productions leave out most of this and cast tall, obviously adult dancers to play Clara and the Nutcracker in the second half, well, I suspect this is why.

To be somewhat fair to Hoffmann, he seems to have run out of steam in his last chapter, more focused on ending the thing than on ending it in a way that made any sense whatever. It’s not just the age thing and the drugging; there’s a very real open question of just how Marie returned from the fairy land, and just what Herr Drosselmeier is up to, beyond introducing her to a fairyland and then mocking her when she tries to tell others about it, and several other huge gaping plot gaps, all of which I’d forgotten about, along with Marie’s age.

Marie’s age wasn’t the only part of the original story that I’d forgotten: the fact that the Stahlbaums have three children, not just two, with a hint that small Marie is a bit jealous of her older sister Louise. The way that Marie accidentally makes fun of Herr Drosselmeier’s looks, the unexpected entrance of about 500 slaves (it’s a minor note) and the way those slaves are used as one of the many indications that not all is well in the candy fairyland. The way that, after Marie tries to tell her parents about what is happening, they threaten to remove her toys completely. The way they urge her not to make up stories, and find imagination dangerous—an echo, perhaps, of what Hoffmann himself had heard as a child.

But above all, just how much of this story is about war, and its effects on family and children: the way Fritz is obsessed with his Hussar soldiers and keeps going back to play with them, and how he insists (backed up by Herr Drosselmeier) that the nutcracker, as a soldier, knows that he must keep on fighting despite his wounds—since fighting is his duty. How just moments after Marie is left alone, when she is trying to heal her nutcracker, she is surrounded by a battle—a battle that leaves her, mostly a bystander, injured. The way that Hoffmann sneaks a fairy tale into the fairy tale that he is telling.

And the way Marie is mocked for telling the truth, and how the men who are using her to break an enchantment—one cast by an injured woman, no less—drug her, gaslight her, and mock her.

They do eventually take her to fairyland, though.

So that’s nice.

I’m also mildly intrigued—or appalled—that a story that spends so much time focused on manipulation, fantasy, and the fierce desire for candy and toys just happened to inspire the music used by multiple retailers to try to sell us stuff every holiday season. It’s a more apt choice than I’d realized.

Anyway. A couple of decades after the publication of Nussknacker und Mausekönig, Alexander Dumas, pere, probably best known as the author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, found himself tied to a chair. Dumas was the sort of person who frequently found himself in those sorts of situations, but this time—or so he later claimed—he was tied there by children, demanding a story. Dumas, by then notorious for writing epically long works, offered to tell them an epic, along the lines of the Iliad, adding “a fairy story—plague upon it!” The kids, shockingly enough, did not want the Iliad. They wanted a fairy tale.

Dumas, who loved adapting (some said, less kindly, outright stealing), thought hard, and told them a version of Hoffmann’s tale. The children were enthralled, and Dumas, a kindly sort, thought it might be nice to scribble down that version in French for their sake, publishing it in 1844—the same year as his wildly popular The Three Musketeers.

At least, that’s what Dumas said. Very unkind people noted that Dumas was short on funds at the time (Dumas was nearly always short on funds at all times) and that an unauthorized adaptation of Hoffmann’s story would be a great way to whip up some quick cash, and it was just like Dumas to blame this sort of thing on innocent kids.

Buy the Book

Finding Baba Yaga: A Short Novel in Verse

I’ll just say that the tied up in a chair makes for a much better story, and that’s what we’re here at Tor.com for, right? Stories. And do we really want to accuse the author of The Count of Monte Cristo of occasionally stretching truth and plausibility just a touch too far? No. No we do not.

In fairness to Dumas, his version of Nussknacker und Mausekönig—or, as he called it, just The Nutcracker—was far more than just a translation. Dumas kept the general plot, and kept Marie seven, but made substantial changes throughout. In his introduction, for instance, Fritz and Marie aren’t hiding in the dark, whispering about possible presents, but sitting with their governess in the firelight—a much more reassuring beginning. Dumas also took the time to explain German customs, and how they differed from French ones, especially at Christmas, and to throw in various pious statements about Christianity and Jesus, presumably in the hopes of making his retelling more acceptable to a pious audience looking for an appropriate Christmas tale, not the story of a seven year old who stays up playing with her toys after everyone has gone to bed and eventually ends up heading to a land of candy and sweets. He also softened many of Hoffmann’s more grotesque details, and adopted a more genial tone throughout the story.

Presumably thanks to Dumas’ bestseller status, this version became highly popular, eventually making it all the way to the Imperial Ballet of St. Petersburg, Russia. It seems at least possible that either it, or the original Nussknacker und Mausekönig, or at the very least an English translation of one of the two versions, came into the hands of L. Frank Baum, influencing at least two of his early books, The Land of Mo (another candy land) and The Wizard of Oz (another portal fantasy). Meaning that E.T.A. Hoffmann can possibly take credit for more than one cultural icon.

But back in 1818, Hoffmann could have no idea that his work would be picked up by a bestselling French author, much less by a Russian ballet company, much less—eventually—inspire the music which would inspire scores of holiday advertisements. Instead, he used the tale to pour out his lingering anxieties and issues about war, and the innocents who get caught up in it along the way—and the refusal to believe their stories. It was something he had learned all too well in his own life, and it gave his tale, however stumbling and awkward the ending, a power that enabled it to survive, however transformed, for centuries.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.